vanitas

solo exhibition at Shower, Seoul, South Korea

August 5—August 27 2023

solo exhibition at Shower, Seoul, South Korea

August 5—August 27 2023

Remembering No-bodies

Exhibition review by Dayun Ryu

A bouquet of scentless flowers. Bodies once in motion, now frozen in time. Pieces of muslin await their final form, while dainty garments of silk charmeuse are preserved in boxes as relics of a past moment. The air is still, and Vanitas, Changhyun Lee’s first solo exhibition at Shower, seems to exist in a state of limbo. Navigating fluidly through time, it presents a medley of intricately crafted objects and images rooted in the rich tradition and history of fashion. These artworks ruminate on the transient nature of human existence through material reproduction, questioning notions of beauty, embodiment, and memory within the age of capitalism.

As if pulled from a couturier’s atelier, the open, unobstructed gallery space holds over 50 recent works by the Seoul-based dressmaker and visual artist. With pieces featuring waistcoats to evening gowns, muslin to silk linen, and roses to ribbons, it becomes clear how Lee’s formal training in fashion design informs not only the material choices but also the conceptual explorations of this exhibition. Here, garments are deconstructed into fabric scraps, narratives, and patterns, and then reassembled as un-wearable sculptures and hazy images. Through this process of transformation and translation, Lee exposes the seams of fashion production as a way to investigate the material value and preservation of the commodified body.

At first glance, the work most clearly associated with conventions of fashion design is Grès Study–Reconstruction of Maison Alix pleated dress Ca. 1938 (2018). This meticulously crafted dress is a reproduction of a 1938 evening gown by Maison Alix using silk jersey on a canvas corset. The detailed pleating is particularly significant as it represents the legacy of Madame Grès, a mysterious French couturier known for her draping techniques using live models to create “living” sculptures. Her innovative approach emphasizes the primary purpose of a piece of clothing, which is fundamentally tied to its relationship with the body—it is designed with the body in mind and fulfills its function when worn. Lee’s take, however, seeks to divulge what remains in the absence of the body. Suspended from the ceiling, the dress hovers mid-air on a stiff corset, as if worn by an invisible figure. Such a display highlights the flowy draping to stand on its own, suggesting an embodiment of a human form without necessitating its physical presence.

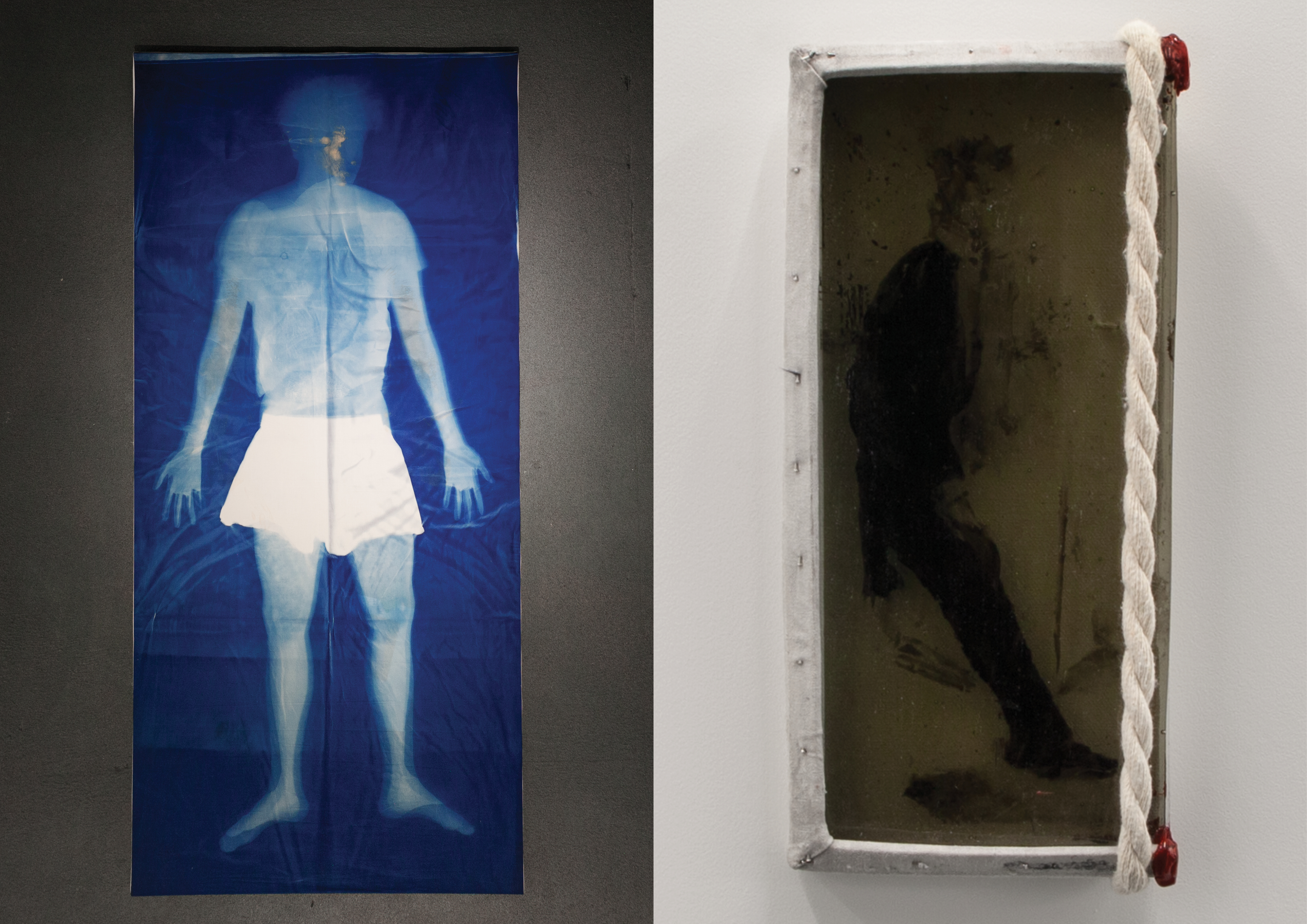

Behind the floating garment, small-scale picture frames line the wall. The delicate frames, each meticulously wrapped in fabric, exude a rather nostalgic flair. The petite frames are like needle boxes tucked away in the backside of grandma’s closet or precious mementos and photographs passed on through generations. Inanimate objects—including needles, fragments of ribbons, heckling, and other items used in making clothes—are carefully arranged inside. Each of these individual tools and fabric scraps is given their own frame and protected behind glass, elevating the rudimentary items from parts of a whole to a preservation of a complete work of its own. Some of these frames are speckled with blood-like reddish blobs, and some display bundles of heckling tied like locks of hair. Again, the crafting hands themselves are not present. Instead, tools and raw materials remain, embodying the crafter’s labor and story. Interspersed among these frames are also pictorial frames, such as Portrait d’un jeune homme (2022), where vestiges of human subjects, who appear to be in the traditional attire of “gentlemen,” are painted with black oil on glass. The transparency of the ghostly images contrasts with the opaque fabric framing them, highlighting the enduring presence of clothing over flesh.

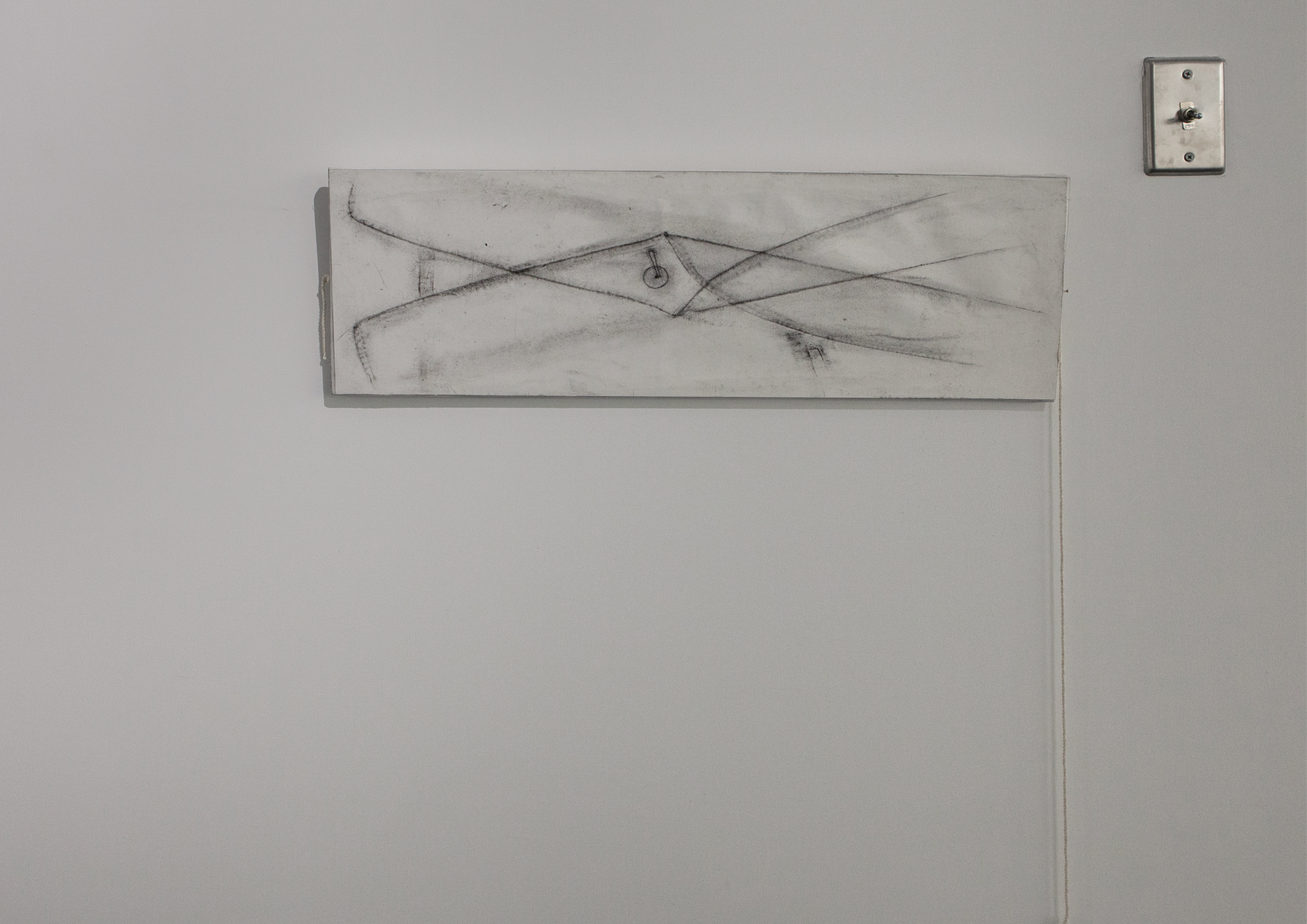

A garment functions as a second skin, both concealing and revealing, embellishing the aging body, accentuating societal standing, and the performance of individuality. Clothing, devoid of bodily presence, then can be said to act as a substitute for its wearer. In Milieu Devant (2023), however, a series of drawings employing the frottage technique to depict a jacket, clothing becomes reduced to an abstraction. Lee rubs specific sections of the jacket’s front (the “devant”), such as the button lining, resulting in its reappearance as crude lines and forms. The transposition of fabric onto paper and a wearable item to rudimentary shapes, presents intriguing juxtapositions. If garments outlast the body, can images further outlive clothing, especially when these images are upheld as “art”? In other words, does the human experience endure through art when the functional aspects of garments become irrelevant and their value is redefined through artistic critique and interpretation?

The artist continues this exploration into the dichotomy of preservation and loss inherent in transforming practical objects into visual representations in Fashion Industry (2023), an artwork that recreates delicate embroidery originating from an 18th century waistcoat. Describing this process as an “autopsy,” Lee effaces the indulgent beauty once favored by France’s royal regime and extracts the ornamental craft of embroidery. Again, the original form of the waistcoat is merely implied, surfacing a composition of elemental floral patterns executed with exquisite precision. By stripping the historical garment of its functionality and reducing it to a purely visual form, the artwork emerges as a detached layer from its former lavish glory. Resting within a box surrounded by stacks of others, one of which includes a silk-dyed flower in an assemblage cage aptly titled Coffin, atop a display table, the set-up evokes a bier and an open casket. In some ways, it hints at both a funeral for the dying art of craft in today’s hyper-economy of fashion and a sardonic commentary on the absurdity of fashion: ultimately, all is vanity.

This satirical homage takes us to the bouquet of artificial flowers, the eponymous artwork of the exhibition. Each flower in the Vanitas sculpture is hand-made from dyed cotton and silk. The flowers and vase are bisected and displayed on a pedestal, inviting viewers to recognize the smooth, blank surface on the other side. There is no deception here; the material composition of the flower outlasts real petals, and the vibrant frontside is contrasted with the stark bareness behind. As indicated by both the title of the artwork and exhibition, Vanitas aligns with the tradition of Vanitas art. This genre of art style, which emerged in 16th-century European still life painting, communicates themes of human mortality and transience through symbolic objects such as flowers, skulls, candles, fruits, and clocks. In Lee’s compelling interpretation, fashion serves as a microcosm where the body is commodified and fetishized for its youthfulness and productivity. The allure of garments conceals life’s fleetingness and substance. In today’s society, where objects often supplant human presence, they symbolically and materially replace the body. Paradoxically, however, the concept of Vanitas reasserts the importance of corporeal essence.

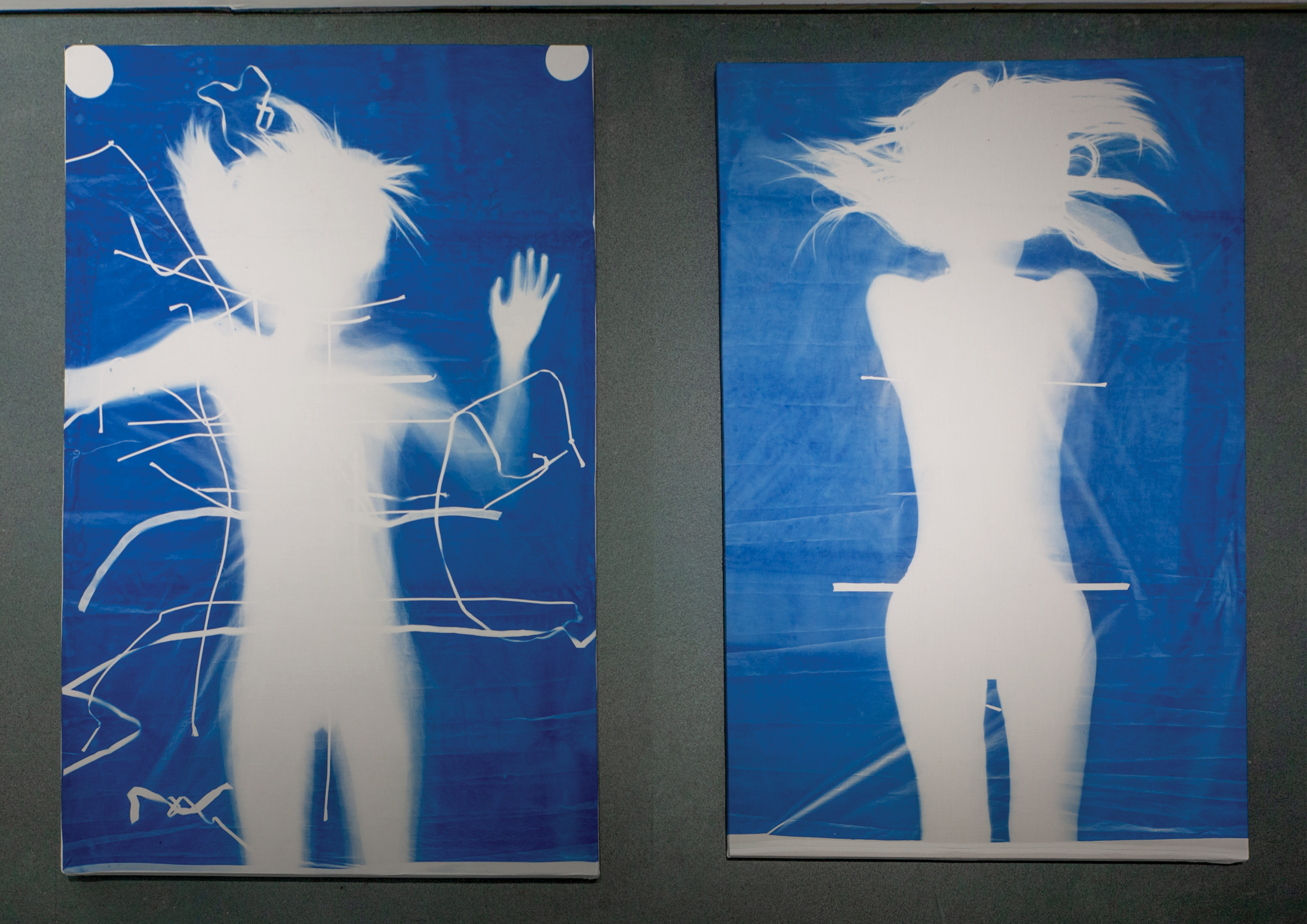

While a sense of stillness pervades the gallery space, filled with fragmented tracings and yet-to-be embodied bric-a-bracs, the display method actively invites the viewer to adjust their proximity to the works. Paper drawings and assemblages are meticulously arranged in an almost uniform line along the perimeter of the gallery, resembling one elongated sentence. Intermittent bursts of clustered artworks on a wall, the display table, and electric blue cyanotypes on the floor punctuate this stagnancy. The drastic contrast in display methods prompts viewers to constantly recalibrate their own physical presence in relation to the artworks. The vibrant cyanotypes of bodies on cotton poplin, laid on the ground, are particularly captivating. As the viewer’s shadow overlaps the white and Prussian blue imprints, a striking interplay of presence and absence emerges. This flitting visual overlay seems to be a poignant and whimsical culmination of Lee’s Vanitas. Peel back the layers, and all that remains is an archive of incorporeal memories, only to be animated by the present moment.

Exhibition review by Dayun Ryu

A bouquet of scentless flowers. Bodies once in motion, now frozen in time. Pieces of muslin await their final form, while dainty garments of silk charmeuse are preserved in boxes as relics of a past moment. The air is still, and Vanitas, Changhyun Lee’s first solo exhibition at Shower, seems to exist in a state of limbo. Navigating fluidly through time, it presents a medley of intricately crafted objects and images rooted in the rich tradition and history of fashion. These artworks ruminate on the transient nature of human existence through material reproduction, questioning notions of beauty, embodiment, and memory within the age of capitalism.

As if pulled from a couturier’s atelier, the open, unobstructed gallery space holds over 50 recent works by the Seoul-based dressmaker and visual artist. With pieces featuring waistcoats to evening gowns, muslin to silk linen, and roses to ribbons, it becomes clear how Lee’s formal training in fashion design informs not only the material choices but also the conceptual explorations of this exhibition. Here, garments are deconstructed into fabric scraps, narratives, and patterns, and then reassembled as un-wearable sculptures and hazy images. Through this process of transformation and translation, Lee exposes the seams of fashion production as a way to investigate the material value and preservation of the commodified body.

At first glance, the work most clearly associated with conventions of fashion design is Grès Study–Reconstruction of Maison Alix pleated dress Ca. 1938 (2018). This meticulously crafted dress is a reproduction of a 1938 evening gown by Maison Alix using silk jersey on a canvas corset. The detailed pleating is particularly significant as it represents the legacy of Madame Grès, a mysterious French couturier known for her draping techniques using live models to create “living” sculptures. Her innovative approach emphasizes the primary purpose of a piece of clothing, which is fundamentally tied to its relationship with the body—it is designed with the body in mind and fulfills its function when worn. Lee’s take, however, seeks to divulge what remains in the absence of the body. Suspended from the ceiling, the dress hovers mid-air on a stiff corset, as if worn by an invisible figure. Such a display highlights the flowy draping to stand on its own, suggesting an embodiment of a human form without necessitating its physical presence.

Behind the floating garment, small-scale picture frames line the wall. The delicate frames, each meticulously wrapped in fabric, exude a rather nostalgic flair. The petite frames are like needle boxes tucked away in the backside of grandma’s closet or precious mementos and photographs passed on through generations. Inanimate objects—including needles, fragments of ribbons, heckling, and other items used in making clothes—are carefully arranged inside. Each of these individual tools and fabric scraps is given their own frame and protected behind glass, elevating the rudimentary items from parts of a whole to a preservation of a complete work of its own. Some of these frames are speckled with blood-like reddish blobs, and some display bundles of heckling tied like locks of hair. Again, the crafting hands themselves are not present. Instead, tools and raw materials remain, embodying the crafter’s labor and story. Interspersed among these frames are also pictorial frames, such as Portrait d’un jeune homme (2022), where vestiges of human subjects, who appear to be in the traditional attire of “gentlemen,” are painted with black oil on glass. The transparency of the ghostly images contrasts with the opaque fabric framing them, highlighting the enduring presence of clothing over flesh.

A garment functions as a second skin, both concealing and revealing, embellishing the aging body, accentuating societal standing, and the performance of individuality. Clothing, devoid of bodily presence, then can be said to act as a substitute for its wearer. In Milieu Devant (2023), however, a series of drawings employing the frottage technique to depict a jacket, clothing becomes reduced to an abstraction. Lee rubs specific sections of the jacket’s front (the “devant”), such as the button lining, resulting in its reappearance as crude lines and forms. The transposition of fabric onto paper and a wearable item to rudimentary shapes, presents intriguing juxtapositions. If garments outlast the body, can images further outlive clothing, especially when these images are upheld as “art”? In other words, does the human experience endure through art when the functional aspects of garments become irrelevant and their value is redefined through artistic critique and interpretation?

The artist continues this exploration into the dichotomy of preservation and loss inherent in transforming practical objects into visual representations in Fashion Industry (2023), an artwork that recreates delicate embroidery originating from an 18th century waistcoat. Describing this process as an “autopsy,” Lee effaces the indulgent beauty once favored by France’s royal regime and extracts the ornamental craft of embroidery. Again, the original form of the waistcoat is merely implied, surfacing a composition of elemental floral patterns executed with exquisite precision. By stripping the historical garment of its functionality and reducing it to a purely visual form, the artwork emerges as a detached layer from its former lavish glory. Resting within a box surrounded by stacks of others, one of which includes a silk-dyed flower in an assemblage cage aptly titled Coffin, atop a display table, the set-up evokes a bier and an open casket. In some ways, it hints at both a funeral for the dying art of craft in today’s hyper-economy of fashion and a sardonic commentary on the absurdity of fashion: ultimately, all is vanity.

This satirical homage takes us to the bouquet of artificial flowers, the eponymous artwork of the exhibition. Each flower in the Vanitas sculpture is hand-made from dyed cotton and silk. The flowers and vase are bisected and displayed on a pedestal, inviting viewers to recognize the smooth, blank surface on the other side. There is no deception here; the material composition of the flower outlasts real petals, and the vibrant frontside is contrasted with the stark bareness behind. As indicated by both the title of the artwork and exhibition, Vanitas aligns with the tradition of Vanitas art. This genre of art style, which emerged in 16th-century European still life painting, communicates themes of human mortality and transience through symbolic objects such as flowers, skulls, candles, fruits, and clocks. In Lee’s compelling interpretation, fashion serves as a microcosm where the body is commodified and fetishized for its youthfulness and productivity. The allure of garments conceals life’s fleetingness and substance. In today’s society, where objects often supplant human presence, they symbolically and materially replace the body. Paradoxically, however, the concept of Vanitas reasserts the importance of corporeal essence.

While a sense of stillness pervades the gallery space, filled with fragmented tracings and yet-to-be embodied bric-a-bracs, the display method actively invites the viewer to adjust their proximity to the works. Paper drawings and assemblages are meticulously arranged in an almost uniform line along the perimeter of the gallery, resembling one elongated sentence. Intermittent bursts of clustered artworks on a wall, the display table, and electric blue cyanotypes on the floor punctuate this stagnancy. The drastic contrast in display methods prompts viewers to constantly recalibrate their own physical presence in relation to the artworks. The vibrant cyanotypes of bodies on cotton poplin, laid on the ground, are particularly captivating. As the viewer’s shadow overlaps the white and Prussian blue imprints, a striking interplay of presence and absence emerges. This flitting visual overlay seems to be a poignant and whimsical culmination of Lee’s Vanitas. Peel back the layers, and all that remains is an archive of incorporeal memories, only to be animated by the present moment.